Over the evening, exposure to screens can seriously harm your sleep: blue light suppresses melatonin and shifts your circadian rhythm, making it harder to fall asleep. You can protect your sleep by using blue-light filters or night modes, dimming screens, and avoiding devices 60-90 minutes before bed. Small changes to your screen habits can produce measurable improvements in sleep quality and daytime alertness.

Key Takeaways:

- Blue light from screens suppresses melatonin and shifts the circadian clock, making it harder to fall asleep and delaying sleep timing.

- Evening screen use is linked to reduced REM and deep sleep and more nighttime awakenings, which lowers overall sleep quality and next-day alertness.

- Mitigate effects by limiting screens 1-2 hours before bed, using night modes or blue‑light filters/amber glasses, dimming ambient lighting, and keeping a consistent bedtime routine.

Understanding Blue Light

When you track why screens affect sleep, blue light is the spectral band (approximately 380-500 nm) most relevant to circadian timing. Shorter wavelengths near 460-480 nm are especially potent at suppressing melatonin and shifting your internal clock. While daytime exposure can boost alertness and performance, nighttime exposure from devices or LEDs can delay sleep onset and fragment deep sleep. Practical mitigation depends on the timing, intensity, and spectrum of light you receive in the evening.

What is Blue Light?

Blue light is the high-energy portion of visible light that your retina uses to signal wakefulness via ipRGCs; exposure in the evening reduces melatonin secretion and shifts circadian phase. Researchers identify wavelengths around 460-480 nm as the most effective at altering sleep timing. Because this band exists in both sunlight and artificial lighting, you need to manage when you get it more than trying to avoid it entirely.

Sources of Blue Light

You get blue light from sunlight (the dominant source), but also from LED and fluorescent bulbs, phone and tablet screens, laptops, TVs, and many smart home devices. Modern display backlights often peak near 450 nm, and bulbs with color temperatures ≥5000K contain noticeably more blue than warm 2700K lamps. Evening exposure from these sources can be particularly disruptive to sleep if not reduced.

Daylight intensity commonly ranges from 10,000-100,000 lux, whereas indoor lighting usually sits below 500 lux, so a daytime walk strongly entrains your clock. Evening, however, holding a phone ~30 cm from your face yields high retinal irradiance; studies indicate 2-3 hours of pre-bed screen use can delay melatonin onset by ~30-60 minutes. Reducing brightness, increasing distance, or switching to warm-spectrum lighting lowers that risk.

Effects of Blue Light on Sleep Quality

Disruption of Circadian Rhythms

Devices emit short-wavelength light (peak sensitivity ~480 nm) that activates ipRGCs in your retina and sends timing signals to the suprachiasmatic nucleus, so evening exposure can phase-delay your circadian clock and push sleep onset later. Research (e.g., Chang et al., PNAS 2015) shows bedtime tablet use delays melatonin onset and next-morning alertness; typical screen use within an hour of bed often postpones sleep by about 15-60 minutes and fragments sleep architecture.

Impact on Melatonin Production

Even short bursts of blue-enriched light in the evening suppress melatonin, lowering peak levels and shifting onset later; studies of e-readers and tablets found measurable reductions in evening melatonin after 1-4 hours of use. If you rely on screens before bed, melatonin suppression varies with wavelength, intensity and duration, so reducing short-wavelength output matters for preserving your hormonal sleep signal.

Mechanistically, ipRGC input to the SCN inhibits the pineal gland’s nighttime melatonin synthesis, with the largest effect when you’re exposed in the 1-2 hours before bedtime. Practical steps that reduce suppression include lowering brightness, shifting color temperature from ~6500 K to ~3000 K, using night filters or amber lenses, and minimizing screen time in that pre-sleep window to protect your melatonin rhythm.

Screen Time and Its Consequences

Prevalence of Screen Use

You’re part of a world where screens dominate daily life: Pew Research found 95% of teens have smartphone access and 45% are online “almost constantly.” Adults routinely use phones, tablets and TVs for hours, with recreational screen time commonly exceeding 6 hours daily. That pervasive use means nighttime exposure is routine rather than occasional, increasing the likelihood that your sleep window will be encroached upon unless you set firm boundaries.

Correlation with Sleep Disorders

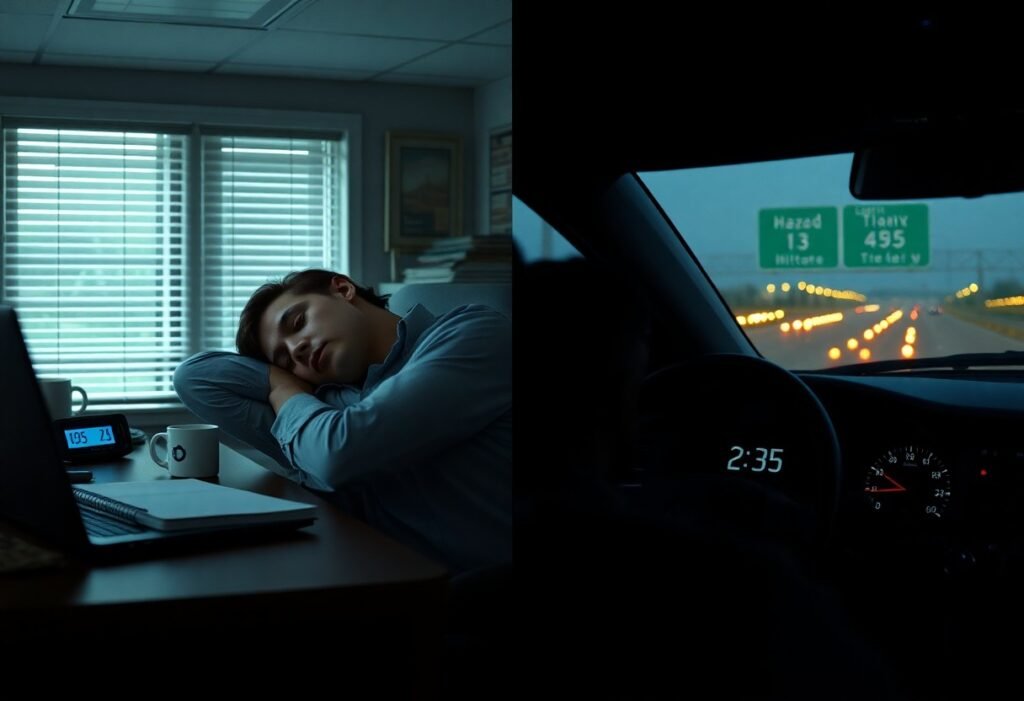

Evening screen exposure correlates with measurable sleep disruption: a Harvard e‑reader study showed that using light‑emitting devices before bed suppressed melatonin, delayed sleep onset, and reduced next‑morning alertness. When you habitually scroll within an hour of bedtime, you tend to fall asleep later and wake less refreshed, raising the chance of accumulating chronic sleep debt.

Beyond immediate melatonin effects, multiple studies link late‑night screen use to objective changes-shorter total sleep time (often 30-60 minutes), lower sleep efficiency, altered REM proportions and more insomnia symptoms. In adolescents, late use is associated with roughly a 25-50% higher likelihood of inadequate sleep, illustrating how routine screen habits can translate into persistent clinical sleep problems if unaddressed.

Practical Strategies for Mitigating Blue Light Exposure

To protect your sleep, focus on concrete steps: stop evening screens 60-90 minutes before bed, switch household bulbs to warm, dim light, and keep bedrooms device-free. Use built-in night modes and app limits so the change is automatic, and follow a 20-30 minute non-screen wind-down. For evidence linking screen use to poorer sleep, see Screen Use Disrupts Precious Sleep Time.

Limiting Screen Time Before Bed

If you end screen use 60-90 minutes before lights-out, your melatonin can rise naturally and sleep latency often shortens. Set device timers, enable Do Not Disturb, or charge phones outside the bedroom to remove temptation. Teens commonly benefit from stricter limits; clinical studies often recommend consistent bedtimes plus a pre-sleep routine of 20-30 minutes without screens to recover lost sleep opportunity.

Using Blue Light Filters and Glasses

Activate device night modes (warm color temperature around 3000K) from sunset to bedtime and consider amber-tinted glasses that block short-wavelength light when you must use screens in the evening. Filters reduce blue wavelength emissions and can make screens less activating; amber lenses worn for 2-3 hours before bed are often used in sleep studies to improve sleep onset.

When choosing glasses, look for lab data showing attenuation of wavelengths below ~500 nm and user-tested comfort; cheap coatings can fail or distort color. Combine lenses with lower screen brightness, warm color temperatures, and a fixed evening schedule for best results. If you have persistent insomnia, trial amber lenses for 1-2 weeks while tracking sleep duration and latency, then consult a clinician with your data.

The Role of Sleep Hygiene

Good sleep hygiene ties daily habits and your environment to sleep quality; you should aim for 7-9 hours nightly and limit evening screen exposure. Shutting off devices 30-60 minutes before bed reduces blue-light-induced melatonin delay, while consistent pre-sleep routines-reading, stretching, or a warm shower-signal your body to wind down. Small changes like these often yield measurable improvements in sleep latency and efficiency within 1-2 weeks.

Creating a Sleep-Conducive Environment

Make your bedroom a sleep-first space: install blackout curtains, cover LEDs, and keep the temperature between 15-19°C (60-67°F). Choose a mattress and pillows that support your posture; if noise is a problem, use a white-noise machine or earplugs. Dim ambient lights and use warm, low-intensity lamps for pre-bed activities to avoid melatonin suppression from bright, cool-toned light.

Establishing a Consistent Sleep Schedule

Set a fixed bedtime and wake time and keep them within 30 minutes every day, including weekends (aim for no more than a 60‑minute weekend shift). Consistency strengthens your circadian rhythm and improves sleep efficiency; adults who maintain regular schedules typically report fewer awakenings and better daytime alertness. Use alarms and deliberate wind-down cues to anchor the routine.

When shifting your schedule, adjust by 15 minutes every 2-3 nights to avoid jet-lag-like disruption, and get 20-30 minutes of morning light to reset your internal clock. Limit naps to under 20 minutes and avoid them after 3pm, track sleep with a diary or app for 2-4 weeks, and seek CBT-I or a sleep specialist if insomnia persists beyond several weeks.

Conclusion

Summing up, exposure to blue light from screens shifts your circadian rhythm, reduces melatonin, and fragments sleep; you can improve sleep by reducing evening screen time, using dim warm lighting or blue-light filters, enabling night modes, and establishing consistent bedtime routines. These steps help restore sleep quality and daytime alertness so you can function better and feel more rested.

FAQ

Q: How does blue light from screens affect sleep physiology?

A: Short-wavelength blue light (roughly 460-480 nm) strongly activates intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs), which relay light information to the brain’s master clock in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. That signaling suppresses melatonin production and shifts circadian timing, making it harder to fall asleep and delaying the timing of sleep. The effect depends on wavelength, intensity, duration, and timing: brighter, longer evening exposure causes larger melatonin suppression and greater phase delay. Content that increases alertness (games, social media, work) adds behavioral arousal on top of the physiological impact.

Q: How long before bed should I stop using screens to protect sleep?

A: For most people, avoiding bright screens for 60-120 minutes before bedtime is a reasonable target to allow melatonin levels to rise and the brain to transition toward sleep. Shorter gaps may help if combined with dimmed displays and low-arousal activities. Children and adolescents are more light-sensitive, so longer screen-free periods and stricter limits are advisable. Individual sensitivity varies, so adjust based on how quickly you fall asleep and how rested you feel the next day.

Q: Do night modes, blue‑light filters, or blue‑blocking glasses actually improve sleep?

A: These interventions reduce short-wavelength light and can lessen melatonin suppression compared with unfiltered screens. Studies show modest improvements in melatonin secretion, sleep latency, and objective sleep measures when filters or amber lenses are used, especially with strong filters and longer evening use. However, benefits are smaller if screens remain very bright or if stimulating content keeps the person alert. Combining filters with reduced brightness, a screen curfew, and calming routines produces more reliable sleep benefits.

Q: What practical strategies reliably reduce screen-related sleep disruption?

A: Effective steps include: set a consistent screen curfew (ideally 60-120 minutes before bed); enable night mode and reduce display brightness and contrast; shift ambient lighting to warmer, dimmer bulbs in the evening; increase physical distance from and reduce viewing time of devices; avoid stimulating content in the hour before bed; use blue‑blocking glasses if evening device use is unavoidable; minimize notifications and late-night work; maintain regular sleep/wake times and a calming pre-sleep routine. Combine multiple measures rather than relying on a single fix.

Q: Who is most vulnerable to screen-induced sleep problems and when should I seek professional help?

A: Children, adolescents, people with delayed sleep phase, shift workers, and those with insomnia or mood disorders are more susceptible to light- and screen-related sleep disruption. Seek medical advice if sleep difficulty persists for several weeks, causes daytime impairment (excessive sleepiness, concentration problems, mood changes), or if basic sleep-hygiene measures fail. A primary care clinician or sleep specialist can evaluate for circadian disorders, provide cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT‑I), or advise on timed light exposure or melatonin treatment when appropriate.